by Amélie Elkik

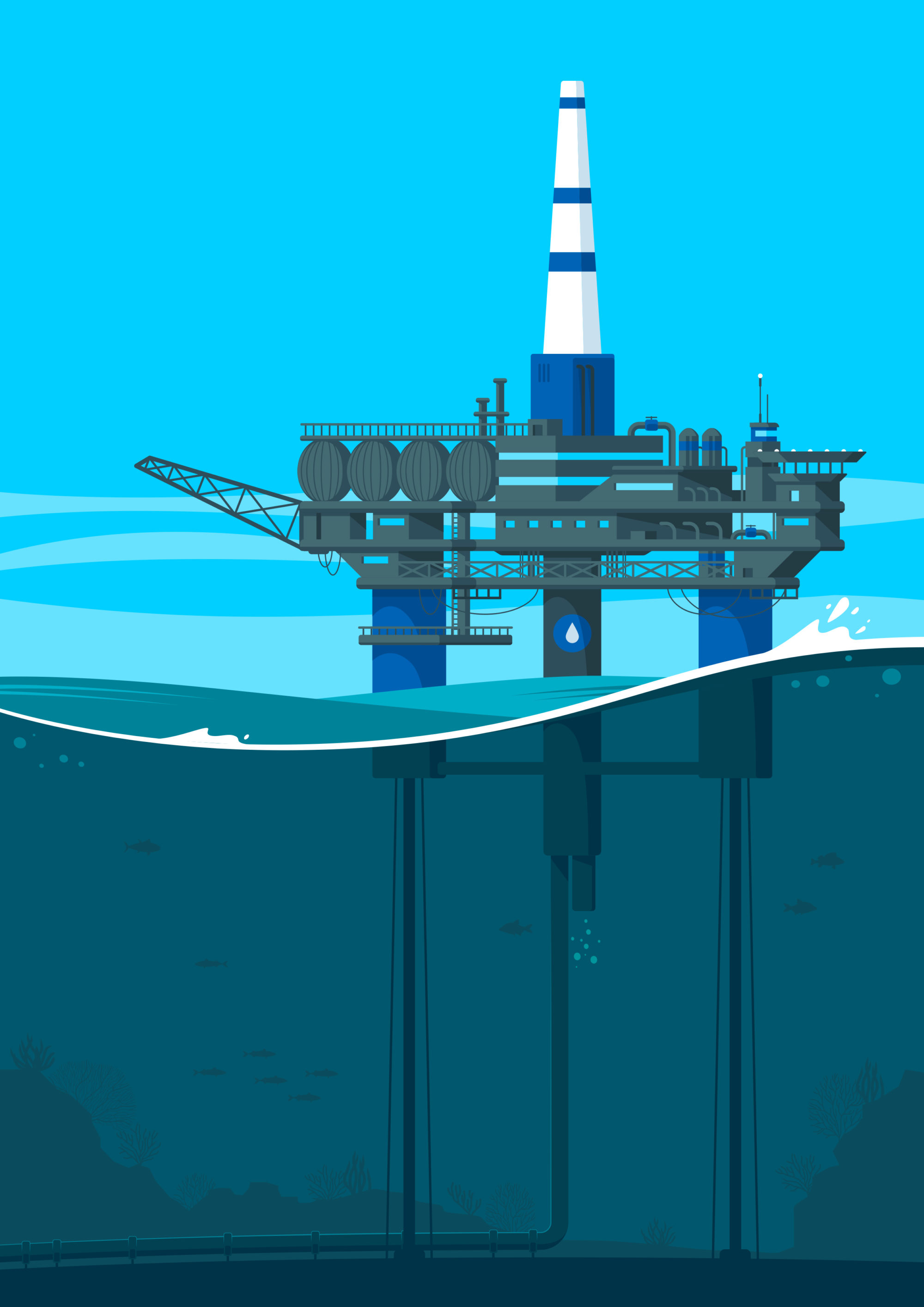

Designed to support production for decades and withstand the most extreme weather conditions, offshore Oil & Gas (O&G) platforms look like a vaguely embarrassing waste when they become obsolete, i.e. when they no longer produce.

The question of final dismantling is only rarely addressed during the design phase and scarcely present in Exploration & Production (E&P) contracts. Nevertheless, the convention asks for a return to the initial status of the site after exploitation.

It is fairly easy to imagine the energy and environmental cost of setting up an offshore oil or gas field, requiring years of engineering and months of installation, with all the required marine drilling, lifting, transport and services.

A decommissioning program also requires long months of engineering and offshore work.

What are, therefore, the cost and environmental impacts of a project to be restored to its original state after 30 or 40 years of production?

Within the first days after the submersion of the oil infrastructures, an underwater settlement started to develop, creating a new ecosystem in place of the old one, suited to the new habitat. Although seemingly inhospitable, a few weeks were enough to create, without prior intention, a concentration of aquatic species, including fauna and flora. The underwater infrastructure, the structural part supporting the platform and the production devices, is mainly made of steel and thus becomes an artificial reef propitious to dense underwater life.

From this underwater point of view, even if we consider that the new colonizing species have driven out the previous ones, is it preferable to wish for a return to the initial state, 40 years back in time, even if it means disturbing everything again?

With regard to the risk of hydrocarbon pollution, the dismantling phase takes place after the cessation of production. There is, therefore, by definition, no risk of hydrocarbon pollution, as the well is “dry”.

Today, the issue of environmental impact and preservation has a strong significance in the concerns of some and the discourses of others.

The question of dismantling oil fields is obviously no more exempt from it than any other subject.

Thus, communications, procedures, reviews and decommissioning engineering will be reworked in the light of this strong dimension.

However, rather than considering the environmental burden as a new parameter that disrupts the already decided and extremely constraining phase of dismantling, sometimes done by merely applying a simple greenish varnish, why not use the opportunity to review the entire decommissioning project and undertake a systemic approach by updating the input parameters, with updated knowledge and means.

Considering the platform as a valuable asset, supporting the development of an activity taking into account judicious parameters, would contribute to reassessing the local and updated added value of these infrastructures.

The pitfall, however, would be to decide too quickly not to dismantle, under the pretext of responsible ecology, and thus avoid any constructive discussion appropriate to the specific context of the decommissioning project.

The environmental issue must remain an integral component of a comprehensive system.