by Amelie Elkik

Oil and Gas Exploration and Production (E&P) is one of the world’s largest, as well as one of the most controversial, activities in terms of world and global challenges.

First, it is a major energy provider and secondly, it involves many decision-making processes: political, geopolitical, economic, financial, technological, ecological, environmental, safety, security and finally, societal.

Activities carried out and required by the oil and gas sector cover, at various levels, a very large part of the world’s industrial fabric: from geophysics to chemistry, and from heavy industry to communications technologies, while necessitating a strong expertise in financial engineering in proportion to the capital invested, the risks considered and the stakes of return on investment.

This requires:

– extremely varied and specialized human resource needs,

– a strict and precise answer to safety and security risks associated with its operation,

– a fine communication policy, increasingly necessary for the management of its reputation.

For many decades, hundreds of billions of dollars have been invested in creating the infrastructure needed to extract, produce, transport and distribute this resource (gas or oil) on world markets.

Not really apparent and of fluctuating interest to stakeholders, the question of offshore oil and gas fields decommissioning is now seen as the end of a highly controversial system in a context that is quite different from the one in place at the beginning of its operation.

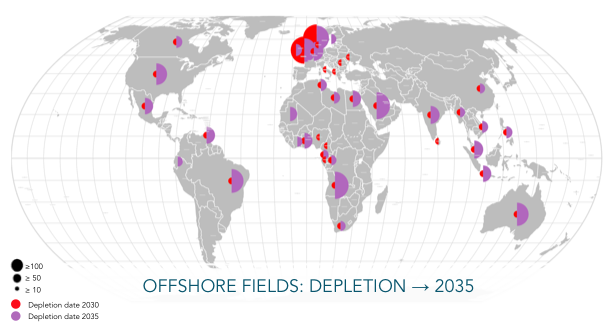

10,000 to 15,000 platforms are currently in operation in all the world’s seas (Gulf of Mexico, Mediterranean & Black Seas, North Sea, Australia, Indonesia, West Africa, South America, etc.).

This represents an average of 200 platforms per year that will cease production by 2035, and for which the question of decommissioning is now a real one.

For the North Sea alone, with approximately 1,500 active platforms with an average age of over 25 years, decommissioning costs are estimated at between $2 billion and $4 billion per year over the next 20 years.

This uncertainty of a factor of 2 on the final costs seems quite surprising given that this is one of the most advanced regions (along with the Gulf of Mexico) in question.

Other regions, such as Indonesia or West Africa, must first clarify the question of contractual responsibility for decommissioning. As for the Persian Gulf, the configuration of “sponge” fields supports the development of “satellites”, extending the life of existing infrastructures and, thus, postponing the question of their final decommissioning.

The postponing of projects and the lack of visibility on medium-term material prices, together with the cost of chartering specialized vessels, the low repeatability of processes and the technical complexity of decommissioning could explain this uncertainty in the final estimate.

Also, in the current context, what arbitration can be envisaged, and will it prove to be judicious?

More generally, this question of decommissioning regulation is not new to the oil industry but is beginning to interest all countries and regions that will have to make the link between field depletion and the potential for land redevelopment in line with their local policies.

However, since the 2000s and the rise of oil prices, the subject had only had relative, even confidential, importance, especially since the quantity of depleted offshore fields was less than today.

As the industry has not yet really organized itself globally, there are a few topics for discussion between the IOC (International Oil Company), international and regional regulatory lawyers, and local politicians.

Although there is no question here of environmental risk linked to hydrocarbon pollution (since the fields are empty), the question of decommissioning may become sensitive from a societal and environmental point of view and, therefore, cannot be politically neutral in a context where the image and purpose of the actors are undergoing major changes.